In West Bengal, the prevalence of stone for construction is notably limited, except for certain areas extending from the Chhota Nagpur Plateau. This dearth of stone has steered builders towards alternative materials, predominantly brick, and has fostered the ascendancy of terracotta as the primary architectural style in the region. The term “terracotta” originates from the Italian words “terra,” meaning earth, and “cotta,” signifying cooked or baked. Therefore, “terracotta” directly translates to “cooked earth.”

Terracotta in Bengal has its roots deeply entrenched in folk art traditions, evolving over time to be recognized as a refined art form, owing to the patronage of the Sultans of Gaur and Pandua. These rulers integrated terracotta into the design of their mosques, elevating its status within the artistic landscape. Subsequently, between the 16th and 19th centuries, Bengal witnessed a proliferation of terracotta temples, marking a significant architectural trend across the region.

Despite this rich heritage, public perception, influenced by imbalanced promotion efforts by government and private tourism entities, often narrowly associates terracotta temples solely with Bishnupur. In reality, these remarkable architectural wonders are scattered across various districts of West Bengal, particularly in the southern regions.

Nestled approximately 9 kilometers to the south of Shantiniketan, within the Birbhum district of West Bengal, lies the quaint village of Supur. This village serves as the humble abode to no fewer than six terracotta temples, each bearing unique cultural and historical significance. Regrettably, only one of these temples has garnered the attention of state authorities for preservation efforts, leaving the others vulnerable to the passage of time and neglect.

The twin temples collectively known as Jora Shiv Mandir are the best examples of terracotta art in Supur, and are easily located on the main road inside the village. Neither temple has a foundation stone so their exact construction date is unknown, although the pioneering terracotta scholar David McCutchion states that all the temples of Supur probably date from the 19th century.

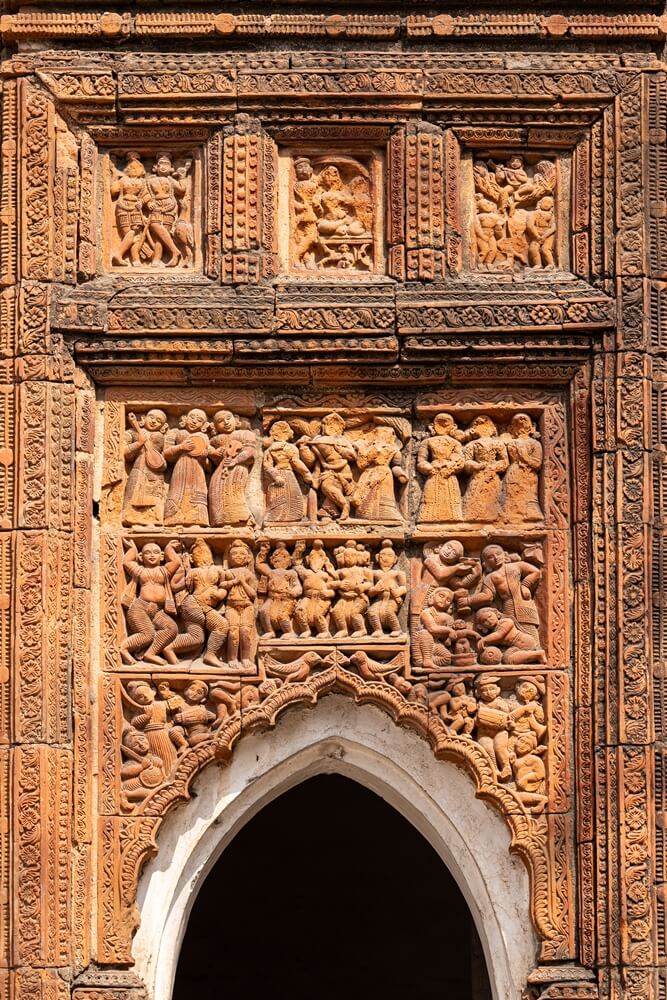

Although the temples are under the jurisdiction of West Bengal State Archeology, there is no noticeboard to assist visitors. The western temple is a square ridged rekha deul with terracotta ornamentation limited to a single panel above the southern entrance, depicting an enthroned Ram and Sita.

Immediately to the east is an octagonal ridged rekha deul, which by contrast has exquisite terracotta on all eight sides, in addition to terracotta motifs covering all the facades.

Terracotta panel above entrance of Jora Shiva Western Temple – Supur

Perhaps somewhat unusual are the repeated themes that occur on the central panels above each of the archways. These depict Chaitanya Maha Prabhu dancing with a bearded man besides him, a five headed man dancing with other individuals, and child being bathed by four women. The bearded man may be Advaita Acharya Prabhu, as out of Chaitanya’s disciples only he had beard. The child seems to be Krishna, but I’m unsure who the five-headed dancing man might be.

The lower panel is also repeated on all eight sides, and depicts primarily musicians, but also dancers and soldiers.

The top panels above the archways are all unique. One depicts a scene from Ramayana, with Rama fighting against his son Lava and Kusha over the Ashwamedh Horse.

Another panel shows soldiers (I assume British?) with guns sitting on an elephant and horses.

Perhaps the most interesting of these unique panels showcases Goddess Durga with her family. It is divided into three sections, with central portion depicting Durga as Mahishashur Mardini with Lakhmi and Saraswati. The faces of the three Goddesses have been unfortunately defaced. Flanking this, Ganesh and Kartick get more prominence here with each having more space, and depicted with woman companions. Ganesh is sitting on a lotus, accompanied by two women, probably his consorts Riddhi and Siddhi. Kartick is seated on his Vahana, the peacock, and is accompanied by a single woman probably his wife Devsena, daughter of Indra.

One of the better preserved arch panel shows Gour Nitai dancing with other followers.

The lower terracotta panels that cover the temple facade also have repeated themes, which is far more usual. Among the common themes are Krishna sitting on Garuda, Krishna with King Bali, Vastraharan scenario and soldiers marching in rows holding guns. Just below the lower panels there is a thin band panel showcasing similar looking faces peering out from round frames.

All of this is enveloped by intricate floral and detailed geometric patterns, which greatly enhances the overall visual impact of the temple facade.

If you’re keen to see what other terracotta temples are in Supur, continue west along the main road and take the track that continues east as the main road abruptly turns right (north). After approximately 200m, this will lead you to an area known as Hattala.

Hattala gets its name from a “haat” or village market that used to happen here at one point in time. There isn’t a market here anymore, and the whole landscape is strewn with piles of bricks, ponds, and overgrown mounds. Some of these mounds are the remains of ruined indigo factories which fell into disuse in the 1850s, the vegetation was so dense that I was dissuaded from exploring them. However, in an area of open ground are two further terracotta temples that can be visited.

The only Pancharatna type temple of Supur can be seen here in Hattala. The temple faces south, but unfortunately most of its terracotta panels are now gone. David McCutchion does mention that this is one of only three examples of a Pancharatna with ridged rekha turrets, single entrance and tri-ratha projections in West Bengal.

Unlike the Jora Shiva temples, the foundation stone still survives here, which gives us a date of 1224 by the Bengali calendar, which translates to 1817.

To the south of the Pancharatna temple is a south-facing Deul type temple which is now quite heavily damaged and many of the terracotta work lost. Clearly at one point this temple was quite impressive, but even the main panel above the arched entrance is now fragmented, which was noted as far back as 1979 by the State Archaeology Department in 1979.

A short distance away next to Shyamsayar Pond is another large Deul type temple with an entrance to the south. Terracotta ornamentation can be found on the southern and eastern faces, but much of the main panel above the southern entrance depicting Ram and Sita has been lost. On the eastern panel there appears to be mostly Vaishnava scenes.

Continuing west beyond the Hattala temples for a further 200m you will reach a small triangular patch of woodland next to a series of ponds. Here stands an old Durga temple, complete with a tree sprouting from the temple roof. In fact, the tree has got such a hold on the temple that it’s hard to make out any masonry at all now, the temple is covered by roots and branches.

It’s very reminiscent of temples often photographed in Cambodia, in particular Ta Prohm at Angkor Wat, albeit on a far more modest scale ! I have failed to glean any information about this structure, other than clearly it has been in existence for quite some time to be found in the state it is in today.

To see the final terracotta temple in Supur you will need to retrace your steps back to the Jora Shiva temples, and continue south for a further 320m.

Located within dense vegetation are the remains of an octagonal flat roofed structure with eight corner turrets and one larger central turret.

Known as the Shyam Rai or Ras Mandir, this temple is in the worst condition imaginable, with one third of the structure completely lost and much more soon to disappear, if it hasn’t already. Any terracotta ornamentation that once existed here has long since gone, and now the temple is precariously balanced on one side by an agonizingly thin column of bricks that surely won’t hold out for much longer under the weight above.

Nearby are the remains of yet more structures, perhaps more industrial in nature and possibly another indigo factory, which seemed to be commonplace in this part of West Bengal.

Indigo, a blue dye derived from plants, has a rich history intertwined with various cultures and economies. Initially rare in Europe during the Middle Ages but abundant in tropical regions, it found prominence through its use by diverse communities, such as the Tuareg people who adorned themselves with indigo-dyed cloth in the Sahara desert. However, it was India that became synonymous with indigo, earning the dye its name “Indikon,” derived from its Indian origin.

The Dutch East India Company pioneered significant imports of indigo to Europe in the 1630s. Yet, their efforts faced opposition from European woad growers, who offered an alternative blue dye. This competition led to widespread bans on indigo, fueled by beliefs of its toxicity in countries like France and England. Despite these hurdles, French entrepreneurs ventured into large-scale indigo cultivation in Bengal in the 1770s, sparking a surge in production driven by the East India Company’s investments.

By the 1830s, private planters, empowered by the Bengal Indigo Contracts Act of 1836, exploited cultivators through oppressive practices. They extended loans at exorbitant rates, compelling farmers to cultivate indigo at meager prices, plunging them into perpetual debt akin to partial slavery.

The culmination of discontent erupted in the 1850s with the publication of Dinabandhu Mitra’s play “Nil Darpan,” exposing the brutality of indigo planters. Subsequent government intervention and the revolt of cultivators led to a decline in indigo cultivation in Bengal, shifting the industry to southern and western India.

However, the advent of synthetic indigo by German scientists in 1897, followed by commercialization by BASF, spelled the demise of natural indigo production in India by 1912, marking the end of an era for the once-lucrative “blue gold” trade.

Jora Shiva Temples

Hattala and Durga Temples

Shyam Rai Temple

Please ‘Like’ or add a comment if you enjoyed this blog post. If you’d like to be notified of any new content, just sign up by clicking the ‘Follow’ button. If you have enjoyed this or any other of my posts, please consider buying me a coffee. There’s a facility to do so on the righthand side of this website for desktop users, and just above the comment section for mobile users. Thank you !

If you’re interested in using any of my photography or articles please get in touch. I’m also available for any freelance work worldwide, my duffel bag is always packed ready to go…

KevinStandage1@gmail.com

kevinstandagephotography.wordpress.com

Categories: India, Terracotta Temples of Supur, West Bengal